The ECB’s meeting on March 10th is shaping up to be one of its most anticipated. Inflation remains far below target and market expectations of future inflation have hardened at very low levels, indicating that investors have lost confidence in the ECB’s ability to fulfil its mandate. The eurozone’s anaemic economic recovery is faltering, which will put further downward pressure on prices, while the weakening world economy will not provide the external stimulus that the ECB hoped for. The central bank needs to be bold and make it clear it will do everything required to raise inflation. Unfortunately, it is likely to err on side of caution, as it has in the past, damaging eurozone growth prospects and calling into question the sustainability of many member-states’ debt burdens.

The eurozone is not alone among developed economies in experiencing a structural growth slowdown in the rate of economic growth or in grappling with excessively low inflation (see Chart 1). But the currency union does have an especially acute structural growth problem: it has only just recovered its pre-crisis size, a far worse performance than other developed economies, including Japan. The eurozone had hoped to piggy-back on strong global demand, but this source of cyclical stimulus is drying up as growth in the global economy weakens and the value of world trade shrinks. The ECB had also hoped that the euro would weaken sufficiently to raise inflation by boosting import prices. But the euro is stronger than the ECB would like, as the prospect of interest rate rises has receded in the US and UK, reducing the attractiveness of the dollar and sterling. And growth in emerging markets has slowed, putting their currencies under pressure.

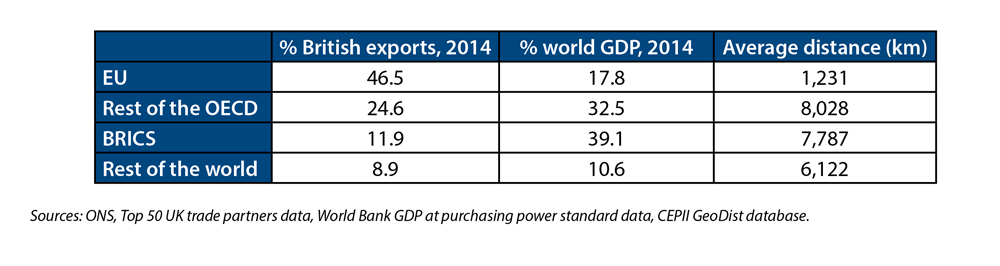

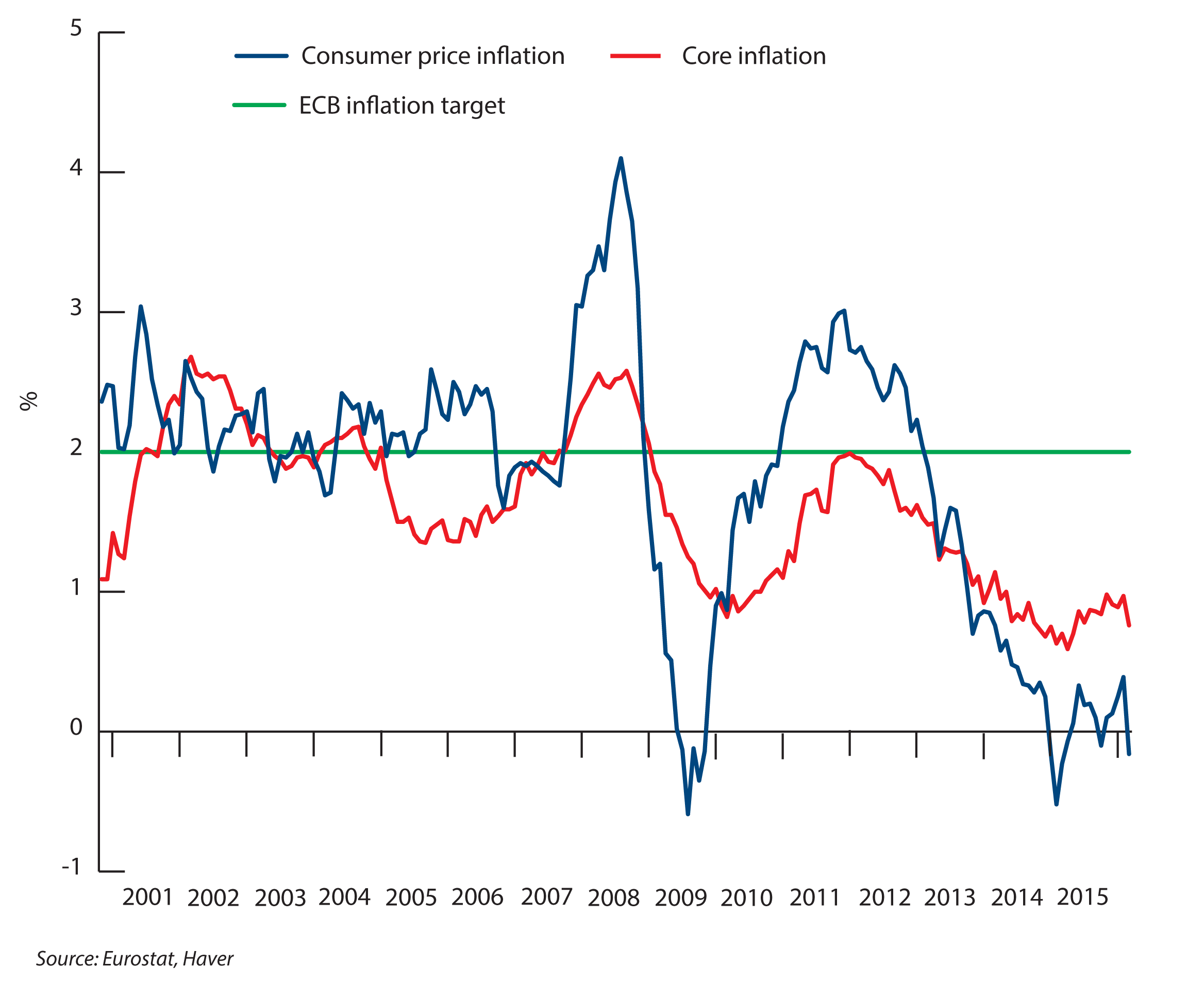

Chart 1: Headline and core inflation in the Eurozone

Weak economic growth is not the only reason for very low inflation in the eurozone. This also reflects the steep fall in oil and other commodity prices, but even stripping out these effects, inflation is far too low: core inflation, which excludes energy and food prices, has been stable at around below 1 per cent (and hence at around half the ECB’s inflation target) for more than two years (see chart). The persistent weakness of inflation is being reflected in lower wage settlements, raising the prospect of a vicious cycle of weak wage growth begetting low inflation and in turn low expectations of future inflation.

The ECB shares quite a bit of the blame for this daunting state of affairs. It has persistently been too optimistic about the outlook for eurozone growth and hence the outlook for inflation. As a result, it was too slow to cut interest rates, and allowed speculation that they could rise at any point. The central bank did eventually launch a major programme of quantitative easing (QE) involving the purchase of a huge quantity of government debt. In the process, it kept a lid on government borrowing costs. But this has not shifted expectations of future inflation, partly because investors are unconvinced that the bank will not reverse monetary stimulus by selling government bonds as soon as inflation picks up a bit. In short, investors do not believe the ECB will do everything possible to meet its inflation target.

The ECB is not entirely to blame for excessively low inflation: the eurozone requires a big fiscal expansion as well as monetary stimulus. Governments should be exploiting unprecedentedly low borrowing costs to step up public investment, boosting demand and growth potential. However, the ECB has consistently argued against fiscal expansion, at least in the absence of a fiscal union. The central bank has moderated its position a little recently, arguing for ‘growth-friendly’ fiscal consolidation, and some board members have even argued that countries with fiscal space to boost spending should use it. But it is opposed to a major eurozone fiscal stimulus.

The ECB has three measures at its disposal to boost growth and inflation. The first is to use the policies it is deploying – the ECB’s main interest rates and QE – more aggressively. For example, it could lower the rate at which banks deposit their reserves at the central bank further into negative territory, from currently -0.3 per cent to -0.75 per cent (the rate prevailing in Switzerland) or even -1.25 per cent (as in Sweden). The ECB could also apply negative interest rates to the loans it extends to banks; the current rate stands at 0.05 per cent. Switzerland and Sweden have already pushed these rates below zero.

Such negative rates would make it less attractive to hold euros and assets denominated in euros. This, in turn, should weaken the single currency –helping eurozone exporters – and drive up inflation. If banks passed on their lower cost of funding to businesses, business investment would become cheaper to finance. Negative interest rates are controversial: they could increase pressure on European banks, which may be reluctant to charge customers for making deposits with them. However, forcing banks to put pressure on large depositors to put their money to better use is welcome. And experience from other countries shows that banks pass on part of their lower rates to customers.

The ECB’s second option is to expand its QE programme (currently €60 billion monthly); broaden its scope to include corporate bonds, bank bonds or even equities; and make it longer – it is due to end in March 2017. The aim of the programme is to lower government funding costs to allow looser fiscal policy, and to lower longer-term interest rates, and hence the cost of borrowing for businesses.

But neither negative rates nor more QE will lift inflation and growth if the ECB does not concurrently change expectations about the future course of monetary policy. Low interest rates alone will not lead to more investment if investors expect economic activity and hence inflation to remain weak. Inflation will rise only if consumers and investors expect that income and output will rise. The ECB needs to convince investors that it will allow inflation to overshoot the 2 per cent target for a while to make up for the period when it failed to meet its target.

Second, the ECB needs to make the overshooting of inflation central to its target. Currently, the ECB targets the rate of change in inflation over the medium term. A period of below-target inflation does not automatically lead the ECB to target higher inflation in order to make up for it. The ECB should commit to a price-level target, promising to reach 2 per cent on average over a rolling period of five years. A period of lower inflation would automatically require higher inflation in the future.

Would a regime change to shift expectations, negative rates and an expanded programme of QE succeed in bringing eurozone inflation back to target? Probably not. After all, the first piece of advice to a central bank in the ECB’s situation is: do not start from here. It is difficult to push a structurally weak economy of the size of the eurozone out of a cycle of low growth and low inflation, especially when external demand is too weak to generate any export-led growth.

The eurozone needs a major fiscal stimulus in order to boost consumption and investment, but eurozone governments are not about to agree on one. However, the ECB could go beyond what any central bank has so far contemplated doing, and hand out cash directly to citizens: so-called helicopter drops. This would almost certainly boost consumption, and help lift inflation. It would legally be difficult for the ECB to implement such a policy, but not impossible.

Alas, the ECB is only willing to consider small changes to rates and its QE programme. The most likely outcome of Thursday’s meeting is a gradual cut in the deposit rate, plus a limited extension of QE. When these measures fail to drive up inflation, there will be another gradual change in policy – but no regime change that is so crucial to changing expectations about the future path of inflation. The ECB will only consider helicopter drops once there is absolutely no alternative, and only then if all other major central banks have already tried them. As a result, the ECB will continue to fail in its duty to ensure an adequate level of inflation across the currency union.

Simon Tilford is deputy director and Christian Odendahl is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform.